I have been reading recently so many of the books of my childhood that I feel I should comment on them even more briefly than I have been doing. After all I must recognize that the joy I feel in renewing pleasures of the past is something I can only just about communicate, without expecting to rouse similar emotions in those who have not experienced such joys.

The books I will look at today are not what might be termed universal favourites, as Enid Blyton or Richmal Crompton’s works are. Indeed, though I enjoyed going back to them, after nearly 60 years, one reason had nothing to do with the books themselves, but related to when I got them, and from whom.

The two books about an eccentric scientist called Professor Branestawm were given me one Christmas by my 5th Lane cousins, their spokesman being, then and for many years before and after, the only girl amongst them, Kshanika. Her older brothers, Shan and Ranil, were 9 and 5 years older, and so we had little in common, though I do recall reading, generally in his room though I was sometimes allowed to borrow them, the comics of Classic books that the latter owned.

Kshanika’s two younger brothers, the nicest in the family, could not however communicate in English, being victims of the monolingualism their mother’s cousin J R Jayewardene had imposed, clear evidence of the absurdity of their mother’s contention when I restarted English medium, that I fussed too much given how good Ranil’s English and mine were though we had been in the Sinhala medium. But the younger two only acquired English when their father sent them abroad for vocational qualifications.

So it was Kshanika who gave me the two Branestawm books, telling me that the Professor was like me, absent minded and chaotic. So he was, and the author, Normal Hunter, laid this on thick.

But there were flashes of brilliance, as when he invented a pancake machine that produced more and larger pancakes, which wrapped themselves round his guests, though the Mayor solidly ate his way through whatever fell in front of him. And all was not lost, for the Council bought the machine to make paving stones.

Then there was the cricket match he arranged, with a bowling machine and a talking wicket, except that both got very excited as the match proceeded. The machine sent down multiple balls, and the wicket made rude remarks when anyone was out. The Vicar and his twin daughters played, though when things got out of hand the Vicar called up the police and the fire brigade, only to find that most of their members were already on the playing field as members of the Pagwell Tradesmen’s team.

Apart from his inventions that would not behave, the Professor’s eccentricity was evinced when he borrowed a book from one of the Pagwell libraries and could not find it when it was due, so he borrowed the same book from another and then another, so that he was rushing around in the fourteen day lending period to return the book and borrow it again so that he could repeat the procedure at another library the next day. It was only when he invited all the librarians to tea that they found different copies of the book shelved under different subjects in the Professor’s library. They wondered why he had fourteen copies of the same book, but decided that he was so clever he read different chapters simultaneously from the different books.

All very much over the top, but I could recall my childhood glee plunging into these during the long afternoon of a Christmas day all those years ago.

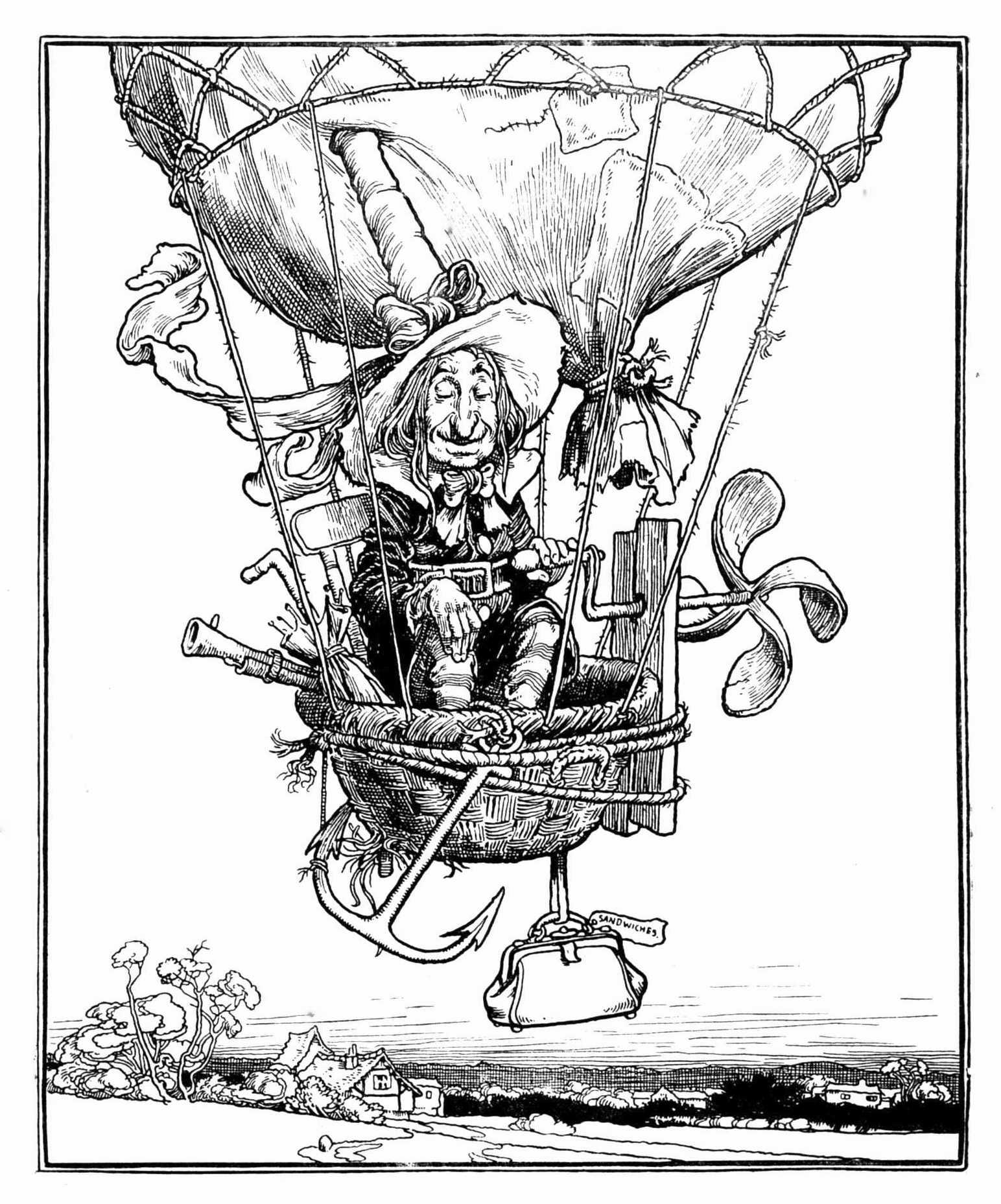

The pictures after the books and the writer are of a Heath Robinson illustration (though not for the Branestawm books) and of Heath Robinson.